Treatments

Secondary breast cancer remains incurable. Therefore, for people living with secondary breast cancer, treatments become a part of everyday life.

There are many different treatment options available for secondary breast cancer. These aim to relieve symptoms and control and slow the spread of the cancer for as long as possible, whilst giving the patient the highest quality of life.

On this page you will find:

-

The main types of treatment for secondary breast cancers

What are “treatment lines” and how are they determined?

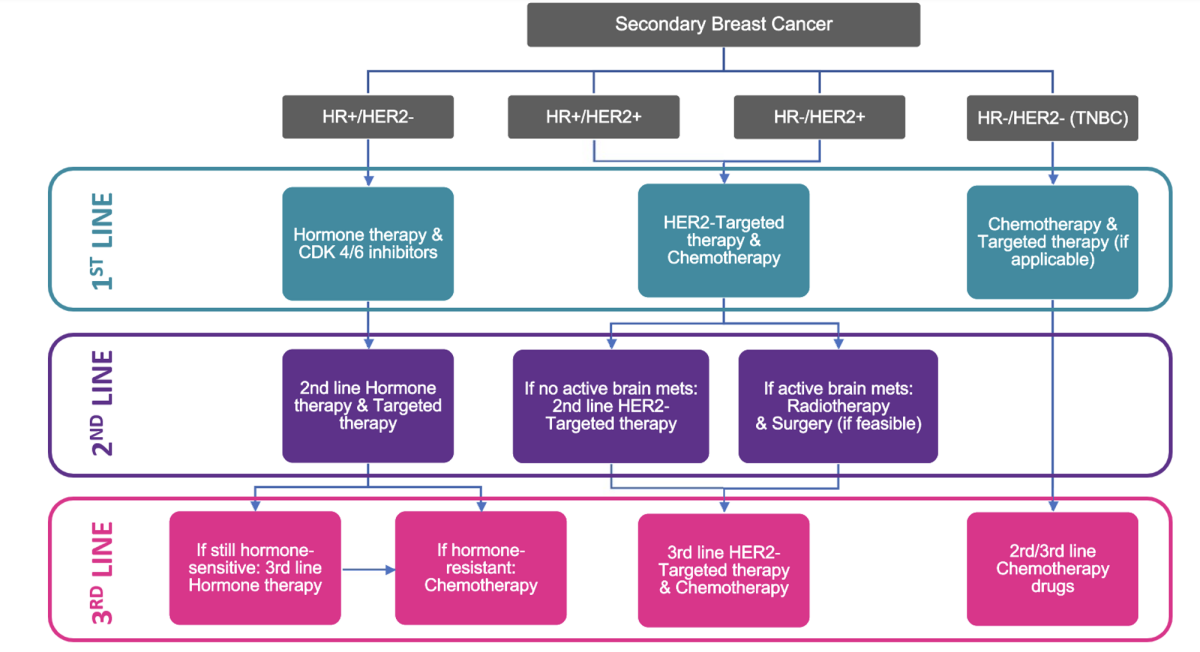

A “treatment line” is whatever type or course of treatment you are currently receiving. Not all treatments are suitable for everyone. Your specific treatment(s) will depend on:

A “treatment line” is whatever type or course of treatment you are currently receiving. Not all treatments are suitable for everyone. Your specific treatment(s) will depend on:

-

The subtype of secondary breast cancer you have

-

How far it has spread and which part of the body it has spread to

-

What treatments you have had so far

-

How quickly your cancer is growing

-

Your general health

Based on this information, your clinical team will determine the most suitable course(s) of treatment(s) to start with. This will be your “first line” of treatment. You will likely continue using this line of treatment for as long as it is effective at controlling your cancer. It may remain effective for several years.

Unfortunately, at some point, your treatment line may stop being effective. At this time, your clinical team will review your case and determine the next most suitable course of treatment for you. This will be your “second line” of treatment, and so on.

Surgery

Surgery may be a suitable option to treat your secondary breast cancer. This involves an operation and a surgeon will remove an area of cancer from your body. Some of the surrounding tissue will also be removed in case there are any cancer cells that have spread into that area.

There are many different types of surgery used to treat secondary breast cancer. Your oncologist and surgeon will talk to you about what type of surgery is best for you depending on the size and number of tumour(s) and where they are in the body.

These are some of the different types of breast surgery you may be offered:

-

Lumpectomy (also known as “breast conserving surgery” or “wide local excision”): A surgeon will remove an area of cancer from your breast and possibly the lymph nodes in your armpit. Find out more here and read about Pam’s experience with a lumpectomy here.

-

Mastectomy: A surgeon will remove all of the breast and possibly the lymph nodes in your armpit. Find out more here and read about Amanda, Linda, and Nikki’s experiences with mastectomies here. You may be able to have breast reconstruction if you want it or have a flat closure if you would prefer (read Juliet’s experience here).

Mastectomy: A surgeon will remove all of the breast and possibly the lymph nodes in your armpit. Find out more here and read about Amanda, Linda, and Nikki’s experiences with mastectomies here. You may be able to have breast reconstruction if you want it or have a flat closure if you would prefer (read Juliet’s experience here). -

Breast reconstruction: A surgeon will reconstruct the shape of your breast after a mastectomy using implants and/or tissue taken from another part of your body. This can be done at the same time as your mastectomy surgery or afterwards. Read more here and read Patricia, Veronica, and Victoria’s experiences here.

-

Oophorectomy: A surgeon will remove one or both of your ovaries. If you are pre-menopausal your ovaries produce most of the oestrogen in your body. If you have hormone receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer, oestrogen will make your cancer grow, so surgically removing your ovaries can help stop the growth and spread of your breast cancer. There are also medications that can stop the body producing oestrogen. Find out more here and read a patients' experience with an oophorectomy here.

Other types of surgery are available depending on where the breast cancer has spread to in your body.

You may need to have chemotherapy or radiotherapy in the time leading up to your surgery. This is to shrink the tumour(s) being surgically removed as much as possible and to prevent further growth and spread. This is known neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs are toxic to cancer cells because they kill cells which are in the process of dividing into two new cells. Cancer cells grow and divide faster than healthy cells in the body and so they are more likely to be killed by chemotherapy drugs. Unfortunately, chemotherapy drugs are also toxic to healthy cells. However, healthy cells are usually able to repair the damage caused by the chemotherapy drugs, whereas cancer cells cannot.

Chemotherapy drugs can help slow the growth of secondary breast cancer cells and control further spread. They can also help relieve some symptoms.

You may receive chemotherapy drugs intravenously (using a needle) or orally (in a pill or tablet form). Chemotherapy drugs then spread throughout your whole body via your bloodstream. You may experience some side effects of this treatment.

You may receive chemotherapy drugs intravenously (using a needle) or orally (in a pill or tablet form). Chemotherapy drugs then spread throughout your whole body via your bloodstream. You may experience some side effects of this treatment.

Electrochemotherapy is a more targeted form of chemotherapy and may be used for secondary breast cancers that have spread to the skin.

A doctor will inject a low dose of chemotherapy drug into or near the tumour. A probe will be placed directly over the tumour to create a small electrical pulse. This electrical pulse briefly creates gaps in the outer wall of the cancer cells and allows the chemotherapy drug to enter the cancer cells much more easily, where it can then kill the cell. Find out more here.

Chemotherapy is usually given as a short treatment once every 1-4 weeks, with a break between treatments to give your body time to recover from any side effects. Chemotherapy is also often given in combination with more targeted therapies. Your clinical team will determine the duration of your treatment combinations for your specific case.

Read real life experiences from our community about different types of chemotherapy:

-

Nab Paclitaxel – Read about Terri’s experience with Nab Paclitaxel here.

-

Carboplatin – Read about Sarah’s experience with Carboplatin here.

-

Epirubicin – Read about Val’s experience with Epirubicin here.

-

Vinorelbine – Read about a patients' experience with Vinorelbine here.

-

Docetaxel – Read about Liz’s experience with Docetaxel here.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy uses a machine to aim high energy radiation at the tumours. The most common type of radiation used is X-rays. Radiotherapy kills cancer cells by destroying their DNA which stops their ability to grow and divide.

Unfortunately, radiotherapy is also harmful to healthy cells, but healthy cells are much better at repairing the damage caused by radiotherapy than cancer cells are. Additionally, modern radiotherapy machines are able to aim precisely at the tumours, therefore reducing the amount of damage to healthy tissue.

The CyberKnife is a machine that can deliver radiotherapy with pinpoint accuracy. It is available at some cancer centres. You can discuss with your clinical team whether CyberKnife is a suitable treatment option for you.

Radiotherapy can help slow the growth of secondary breast cancer cells and control further spread and is often given in combination with other targeted therapies. Radiotherapy can also help relieve some symptoms.

Radiotherapy treatment itself is not painful, but you may experience some side effects afterwards. Radiotherapy is usually given as a series of short treatments every day (Monday to Friday) with a rest at the weekend. This usually continues for several weeks. The type of radiotherapy and the length of your treatment period will depend on the location, size and type of cancer.

Radiotherapy for secondary breast cancer is most commonly used when the cancer has spread to the bone (bone mets), brain (brain mets), or to relieve spinal cord compression caused by bone mets in the spine putting pressure on the spinal cord.

Hormone Therapy

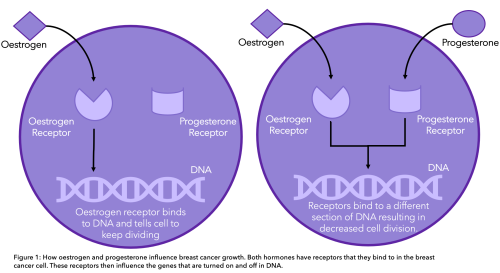

Hormone receptors sit on the outside of breast cancer cells. When they connect with certain hormones in your body (oestrogen and/or progesterone), it tells the cancer cell to grow (Figure 1).

Hormone therapies are used if your cancer is oestrogen receptor positive (ER+) and/or progesterone receptor positive (PR+) and is therefore known as hormone receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer.

-

80% of breast cancers have oestrogen receptors (ER+), 65% of those also have progesterone receptors (PR+)

-

Some people may have ER-/PR+ breast cancers, but these are rare

-

All are considered HR+

Understanding the hormone receptor status is important in deciding on a treatment plan because hormone therapies can target the specific type of hormone(s) that your cancer responds to. These treatments block the hormones from attaching onto these receptors and therefore stop the cancer from growing and spreading.

Understanding the hormone receptor status is important in deciding on a treatment plan because hormone therapies can target the specific type of hormone(s) that your cancer responds to. These treatments block the hormones from attaching onto these receptors and therefore stop the cancer from growing and spreading.

Unfortunately, because hormone therapies work to reduce the amount of oestrogen in your body, you are likely to experience menopause (or if you are already post-menopausal, to experience menopause-like symptoms). To find out more, read our webpage on secondary breast cancer and menopause.

There are many different types of hormone therapies, each working in slightly different ways. Your oncologist will determine which treatment is most suitable for your specific case.

You may receive hormone therapy drugs intravenously (using a needle) or orally (in a pill or tablet form).

Some common hormone therapies include:

-

Anastrozole, which is an aromatase inhibitor

You may receive hormone therapy in combination with other types of treatment. For example, you are likely to take CDK4/6 inhibitors alongside your hormone therapy because these make treatment more effective.

Targeted (biological) therapies

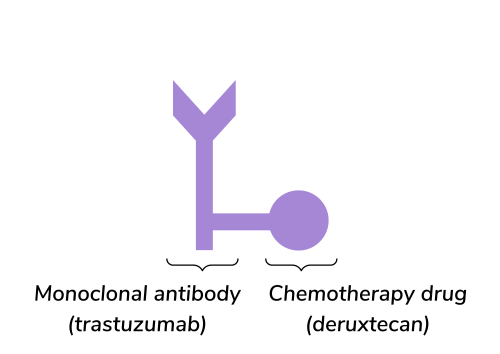

Targeted therapies work to kill specific types of cancer cells by interfering with the things that cause them to grow and spread.

Targeted therapies include a broad range of different treatments that work by targeting specific characteristics (e.g., genetic mutations) of your particular type of cancer. Not all targeted therapy drugs will be effective for all types of cancer. Your oncologist will test the characteristics of your cancer, and this will help them identify the best treatment plan for you. You may also receive targeted therapy in combination with other types of treatment.

For example, some breast cancers have too much of a receptor called HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). This is called HER2 positive (HER2+) breast cancer. Extra HER2 receptors cause cancer cells to grow quickly, so targeted treatments are designed to block the HER2 receptor.

Other types of targeted therapies include immunotherapy, which helps your immune system to recognise and attack cancer cells.

Some common targeted therapies include:

-

Trastuzumab (Herceptin®)

Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) -

Trastuzumab emtansine (KADCYLA®)

-

Trastuzumab deruxtecan (ENHERTU®)

-

Pertuzumab (PERJETA®)

-

Everolimus (Afinitor)

-

Ribociclib (Kisqali®)

-

Palbociclib (IBRANCE®)

-

Sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy®) which is often used to treat people with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC)

Because targeted therapies are specific to the characteristics of cancer cells, they are less likely than other treatments to harm healthy cells.

You may receive targeted therapy drugs intravenously (using a needle) or orally (in a pill or tablet form).

What if my current treatment line fails?

If your current line “fails,” it means that your cancer has continued to grow and spread despite your current treatment.

When this happens, your oncologist will reassess the condition of your cancer and help you decide on the best next line of treatment.

They will take several factors into consideration:

-

What previous therapies you have received and your response to them

-

Specific biological characteristics of your cancer (e.g., genetic mutations, treatment resistance)

-

Current progression of your cancer (e.g., whether it is actively spreading)

-

Side effects of potential next treatments

-

Availability of potential next treatments through clinical trials

Shared decision making allows you to discuss your treatment preferences and how the side effects of different treatments may affect your daily life, so you can come to a joint decision with your clinical team about the best next line of treatment for you.

Written by Clare McDonald, University of Edinburgh

Reviewed by Dr Sarah Thomas, Make 2nds Count

Date of last update: April 2024